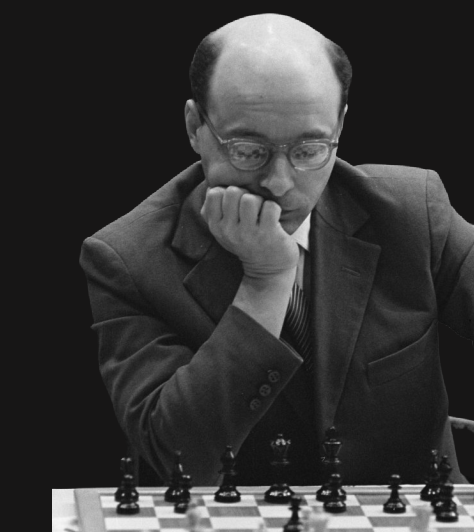

David Bronstein: Kyiv Chess Dynamo

Having grown up during the time when the USSR dominated the chess world, I have to admit that the subtle distinctions between Russian, Soviet and Ukrainian have largely eluded me. Whether Latvian (Mikhail Tal), Armenian (Tigran Petrosian), Estonian (Paul Keres) or Ukrainian (Leonid Stein), they all ended up representing the virtually invincible Soviet team. Having in a previous article said that Stein was the best of Ukrainians, I am now reminded that David Bronstein and Isaac Boleslavsky were also from Ukraine.

David Ionovich Bronstein was born on February 19, 1924 in Bila Tserkva, Ukraine. When Bronstein was six years old, his grandfather taught him to play chess. Later his family moved to kyiv (now Kyiv); there he joined the city chess and checkers club, quickly winning the Kyiv Schoolboys Championship. At the age of 16, he was invited to the 12th Ukrainian Championship, again in Kyiv, where he won the silver medal behind the established grandmaster. Isaac Boleslavsky. This fine result qualified the young Bronstein both for the title of Soviet national master and for a place in the semi-finals of the USSR championship in Rostov-on-Don. This was never concluded, due to the German invasion of the USSR on June 22, 1941.

Nevertheless, after 1945, Bronstein’s immediate career was meteoric. With FIDÉ, the world chess federation, which now organizes the world championship on regular three-year cycles, Bronstein won the 1948 Interzonal, a key qualification on his way to the supreme title. He then shared 1st in both USSR Championship (1948) and the USSR Championship (1949)then tied with Boleslavsky for 1st in the Candidates from Budapest (1950), winning the next playoff game. Bronstein had now earned the right to face the Red Tsar of Soviet chess, Mikhail Botvinnik in a world title bout.

This match turned out to be one of the most controversial in the entire history of the World Chess Championships. Indeed, this may have fueled Bobby Fischer’s later accusations of match-fixing by Soviet players. The conundrum here is why either player should commit to a fixed outcome, when the main prize, the World Champion accolade, outweighs any possible alternative compensation that might have been offered. ? First, here’s some family history.

According to Chessgames.com, the NKVD (later the KGB) arrested Bronstein’s father in 1935 for “trying to defend peasants…who were being pressured by corrupt officials”. Bronstein’s father was released after serving seven years in a gulag and was not rehabilitated until 1955. Bronstein never joined the Communist Party, or any organization associated with it, such as the Youth Party communist, the Union of Writers of the USSR or the Union of Journalists of the USSR.

With two games to play in the 1951 title match against Botvinnik, Bronstein led by one point, but in the 23rd and penultimate game the young challenger mysteriously quit in a position that even modern computers have not seen. failed to prove a conclusive victory for Botvinnik.

The latest modern computer analysis indicates that Bronstein (from the position on the chart where he actually quit and therefore more or less gave up hope of winning the game) probably could have held on with that crafty defense. Black’s pawn sacrifice at move 57 (instead of giving up) is necessary to be able to continue with 58…b6, thus eliminating the vulnerable target at b7.

57…b5 58. axb5 b6 59. Kd3 Ng8 60. Bxd5 Nf6 61. Bc6 Kf5 62. Kc4 Nd6+ 63. Kb4 Re6 . And Black may be able to establish a fortress. At the very least, it should have been tried. Although more recent analyzes establish an arguably superior line for White… 57…b5 58. axb5 b6 59. Kd3 Ng8 60. Ke3!Nf6 61. Kf4 Nd6 62. Be2 Nfe4 63. Bd3 Kg7 64. Be7 Nc8 65. Bd8 Nc3 66. Ke5 Kf7 67. Bf5 Na7… it remains inexplicable why Bronstein quit the moment he did.

The 24th and final game failed, the score was 12-12 and Botvinnik retained his title. Did Bronstein fear official repercussions if he won? Worry about this outcome seems highly unlikely. Fate had called Bronstein, but when the celestial phone rang, he hung up.

As a player, Bronstein, with his brilliant combinatorial and sacrificial gifts, was a true heir to Alexander Alekhine. The Russian émigré had died as an undefeated champion in 1946, giving FIDÉ its chance to take democratic control of the championship.

Bronstein also made considerable creative contributions to the theory in such overtures as the Ruy Lopez (e.g., against Paul Keres), the King’s Indian, which he virtually invented in its modern form (two founding examples: against Frantisek Zita and against Ludek Pachman) and the Caro-Kann (e.g. the Bronstein-Larsen Variation 1.e4 c6 2.d4 d5 3.♘c3 dxe4 4.♘xe4 ♘f6 5.♘xf6 gxf6). (Again, two examples: versus Istvan Bilek and also Nikolai Bakulin).

Bronstein once said that: “The art of a chess player consists in his ability to kindle a magic fire from a dull and insane position.” I conclude with one last facet of Bronstein’s genius, his ability to strike at the optimal psychological moment. In the next game against SmyslovBronstein is being gradually worn away, until he ingeniously muddied the waters with the wild sacrifice Nb4.

Bronstein’s fantasy portfolio is so rich that there are still plenty of other games that command both admiration and inspiration. Try the following for pure glare.

Raymond Keene’s latest book “Fifty Shades of Ray: Chess in the year of the Coronavirus”, featuring some of his best pieces from TheArticle, is now available at

by Blackwell

.

A message from the article

We’re the only publication committed to covering all angles. We have an important contribution to make that is needed more than ever, and we need your help to keep publishing through these tough economic times. So please donate.

Comments are closed.