The war on terror America is winning

[ad_1]

Since the September 11 attacks, the United States has started wars in Iraq, Afghanistan and elsewhere, part of a war on terrorism that has publicly focused on invasions and insurgencies. As evidenced by the US withdrawal from Afghanistan, these militarized counterterrorism efforts have stalled somewhat in recriminations and regrets.

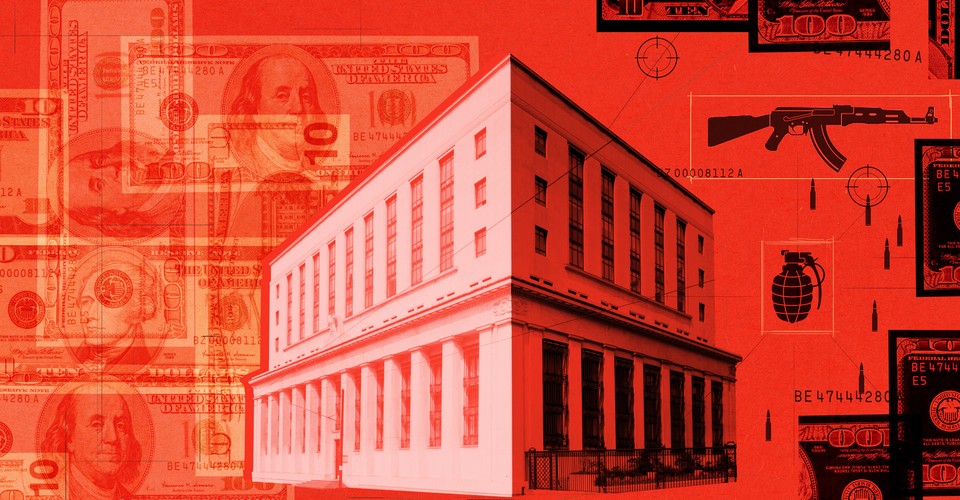

At the same time, the United States has made efforts to weaken terrorist groups through a separate approach, which appears to be the most successful. It is a battle of financial access, not of armaments, and is fought by bureaucrats, not soldiers. This campaign to stop terrorist financing offers more cautious optimism, as well as a way forward: we can use markets, rather than just the military, to reduce terrorists in the 21st century.

Billions of dollars pass through the global financial system every day. Most of these transfers are trivial: investors buying foreign stocks or migrants sending money home. But among the incrustations and the expense lurks something more infamous: money intended for terrorists and criminals.

These illicit funds rub shoulders with legitimate exchanges, passing through sometimes indifferent financial institutions. Some cross-border transfers: the offshore secret account of a Gulf prince or the hawala vendor down the street – maybe all a terrorist group needs to plan their next attack. The Islamic State attacks in Paris, for example, cost less than $ 10,000, but left 128 people dead.

Large-scale operations take more time, planning and funds. Al Qaeda spent nearly half a million dollars in the years leading up to the 9/11 attacks, much of which went to U.S. bank accounts to purchase training and flight supplies. Yet no transfer has been reported as suspicious.

The United States has disproportionate market power, claiming the world’s largest economy and largest financial sector. Its currency is used in transactions around the world. And even before September 11, it had a framework to stop illicit flows, using laws and regulations to target money from drug cartels and organized crime.

Tackling the kind of small-scale transfers that support terrorism, however, has required a new global boost.

The initial effort began just days after September 11. The fight against the financing of terrorism has been declared a top priority, as important as the fight against al-Qaeda itself. The PATRIOT Act imposed new banking laws, establishing a host of financial transparency requirements: US financial institutions now had to know who they were doing business with and screen those customers for potential risks. Banks had become tools of national security.

Treasury officials knew, however, that this approach had an underlying problem. Despite its disproportionate influence, the United States alone could not prevent the questionable money from finance. The World Bank is like a network of underground tunnels: blocking one passage only redirects traffic to other roads.

The Bush administration, which likes to go it alone in other ways, has turned to multilateralism to solve the problem. Within weeks, the United States added new names to a United Nations sanctions list targeting al Qaeda and passed a broad Security Council resolution demanding that all countries criminalize terrorist financing. In a separate international forum called the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), Washington rushed the adoption of special recommendations detailing precisely how countries should end terrorist financing.

The actions of the UN Security Council are binding under international law, and by acting through the UN, the United States has forced other countries to freeze the assets of likely terrorists and adopt new laws and regulations. The PATRIOT Act, meanwhile, gave the US Treasury carte blanche to deploy financial coercion; Washington could now maintain its own sanctions list against terrorist threats. And through the FATF, the United States could exercise information power, collecting and disseminating best practices.

Law, coercion, and information were all viable strategies of influence, but all three started and stalled. Countries have struggled to implement the UN asset freeze and have delayed passage of anti-terrorism legislation. The laws that were passed generally had glaring loopholes. Ignoring the FATF’s list of best practices, national parliaments have tended to criminalize only illicit flows directly linked to a terrorist act, an important limitation because, with funds being fungible, monetary support could continue unchecked.

The sanctions route has encountered other problems. In the early years, the Treasury was willing to list a few countries – Ukraine, Nauru and Burma – for illicit financing issues. But a decade later, the list was seldom used. The United States may have had disproportionate financial power, but that couldn’t offset the political costs that came with unilateral sanctions: targeting a few bad apples was fine, but what if the problem was an ally of the United States , as was often the case?

After years of limited progress, the then 34 FATF members decided they needed a better way to tackle illicit financing. The organization was monitoring politics, but too many countries were falling behind. He decided he would publish a public list. If a country, like Turkey or Indonesia, did not do enough to stop illicit financing, the FATF would make it known.

Officially, the FATF has rarely threatened to punish the listed countries; these efforts were reserved for major issues such as North Korea and Iran. Unofficially, however, the list was a signal to global banks. The listed countries began to face higher banking costs or delays in trade finance. The FATF might have called for few explicit consequences, but banks were stepping in to enforce FATF standards. The listing of Panama, for example, has led some international banks to suspend their relations with Panamanian banks. In Thailand, the country’s list meant diplomats struggled to cash checks.

So while defense officials planned and led invasions in Iraq and Afghanistan, Treasury officials worked to transform the financial system into a place where banks around the world would scrutinize illicit flows.

In 2009, more than 80% of countries either had no laws criminalizing terrorist financing or laws with significant loopholes. Today, almost all countries have a comprehensive legal framework. The FATF has accomplished what law and unilateral coercion could not: a radical change in the way countries approach terrorist financing.

The application of the market is based on a keen understanding of power in the modern age. Seventy years ago, the US government used financial aid to Europe to offset the Soviet Union. The plan linked economic growth and trade to long-term security gains. Fast forward to today, and these ties have evolved into a global system in which governments fear the daily vagaries of international finance and trade more than the distant possibility of another world war.

Those who have the power to influence the markets therefore have the capacity to change the world. The United States has dominated this space for many years, but policymakers don’t seem to be aware of the power they have. National security conversations remain focused on weapon systems and alliances; those focused on climate change suggest a passive acceptance of the status quo. But markets have their own kind of influence and authority that can be wisely wielded.

America’s power is slowly declining, the world stage becomes more and more crowded every year, and non-traditional solutions are more essential than ever. One of these solutions, the market application, has a deep and broad global reach. Its impact, however, rests on a multilateral approach. By acting through the FATF, the United States has avoided many political costs that would make it difficult to pressure its allies to fight illicit financing. U.S. regulators could shape banking incentives, but the economic clout of FATF members ensures that banks around the world are part of this effort.

Multilateralism can also help protect market enforcement from itself. Market power, once released, is not easy to control. When governments tinker with profit functions, they signal priorities that can undermine other important values. The fight against illicit financing means that banks are less willing to support low-yielding customers. Thus, rules that make it more difficult for a supporter to funnel money to the Somali terrorist group al-Shabaab have also made it more difficult for ordinary Somalis to receive aid and remittances. What costs are acceptable? And how to minimize them? Such conversations cannot take place without broad engagement.

The United States’ counterterrorism policy has left us all with great regrets. We cannot correct the mistakes of the past two decades, nor make what is happening in Afghanistan any less painful to watch. But by understanding the form of all possible things, we can honor those who have died.

For too long, the US government has viewed national security as best achieved through war, bombing, and coercion. But we are in a different time, and the political solutions of the past 100 years are ill-suited to the threats of the 21st century. Market enforcement can be a key to pushing us into a new foreign policy moment. It is only by seeing our successes that we can avoid repeating our failures.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we get a commission. Thank you for your support Atlantic.

[ad_2]