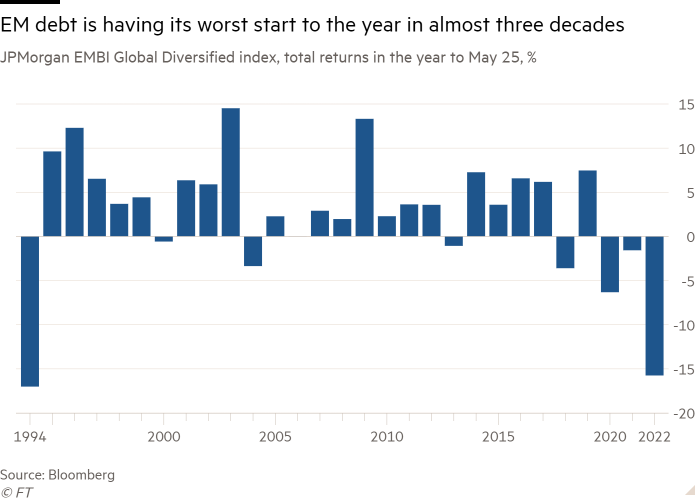

Emerging markets hit by worst selloff in decades

Emerging market bonds are suffering their worst losses in nearly three decades, hit by rising global interest rates, slowing growth and the war in Ukraine.

The benchmark for dollar-denominated emerging market sovereign bonds, the JPMorgan EMBI Global Diversified, has generated total returns of around minus 15% so far in 2022, its worst start to a year since 1994. The decline was only slightly dampened by the broad rally in global markets in recent days, which ended a seven-week losing streak for Wall Street stocks.

Nearly $36 billion has flowed out of emerging markets mutual and bond funds since the start of the year, according to EPFR data; stock market flows have also reversed since the beginning of the month.

“This is definitely the worst start I can remember in the asset class and I’ve been doing emerging markets for over 25 years,” said Brett Diment, head of global emerging market debt at Abrn.

Developing economies have been hit hard by the coronavirus pandemic, putting a strain on their public finances. Rising inflation, slowing global growth, and geopolitical and financial disruption caused by Russia’s war in Ukraine have added to the economic pressures they face. Investment outflows threaten to compound their woes by tightening liquidity.

David Hauner, head of emerging markets strategy and economics at Bank of America Global Research, said he expects the situation to get worse.

“The big story is that we have so much inflation around the world and monetary policymakers continue to be surprised by how high it is,” he said. “That means more monetary tightening and central banks will keep going until something breaks, the economy or the market.”

Yerlan Syzdykov, global head of emerging markets at Amundi, said rising yields in developed markets like the United States – driven by rising central bank rates – are making emerging bonds less attractive. “The best you will earn zero, the worst you will lose money [this year],” he said.

Hauner said rate hikes in major developed market economies were not necessarily bad for emerging market assets if accompanied by economic growth. “But that’s not the case now – we have a major stagflation problem and central banks are raising rates to kill runaway inflation in some places, like the US. It’s a very unhealthy backdrop for investors. Emerging Markets.

China, the world’s largest emerging market, faced some of the biggest sales.

Worries over geopolitical risk, including the possibility of China invading Taiwan following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, have been heightened by the economic downturn as the government imposed draconian lockdowns in pursuit of its zero-Covid policy, said Jonathan Fortun, an economist at the Institute of International Finance, which monitors cross-border portfolio flows to emerging markets.

Chinese assets have received large so-called passive inflows over the past two years, he noted, following the country’s inclusion in global indexes, meaning fund managers trying to mirror their indexes benchmark automatically bought Chinese stocks and bonds.

This year, however, those flows have reversed, with more than $13 billion in Chinese bonds in March and April and more than $5 billion in Chinese equities, according to IIF data.

“We expect negative outflows from China for the remainder of this year,” Fortun said. “It’s a very big deal.”

Fund managers failed to allocate some of the money taken out of China to other emerging assets, he said, leading to a widespread pullback: “Everyone is turning away from whole complex is emerging as an asset class and moving towards safer assets.”

The shock to commodity prices caused by the war in Ukraine has increased pressure on many developing countries that depend on imports to meet their food and energy needs.

But it also made winners among commodity exporters. Diment d’Abrn noted that while local currency bonds in the JPMorgan GBI-EM Index have generated total returns of minus 10% so far this year in dollars, there is wide divergence between countries.

Bonds issued by Hungary, which is close to war and dependent on Russian energy imports, have lost 18% since the start of the year. Those of Brazil, a major exporter of industrial and food raw materials, are up 16% in dollars.

Diment said emerging market debt valuations “arguably look quite attractive now” and Abrdn has seen sharp inflows so far this year into its emerging market debt funds.

However, Bank of America’s Hauner argued that the bottom will only be reached when central banks shift their focus from fighting inflation to promoting growth. “It may happen in the fall, but we don’t feel like we’re there yet,” he said.

Syzdykov said it hinged on inflation falling, bringing the global economy back to a balance between low inflation and low interest rates. The alternative is for the United States to slip into recession next year, adding to global growth and pushing emerging market yields even higher, he warned.

Comments are closed.