Ukraine and Syria top Lavrov’s agenda in Turkey

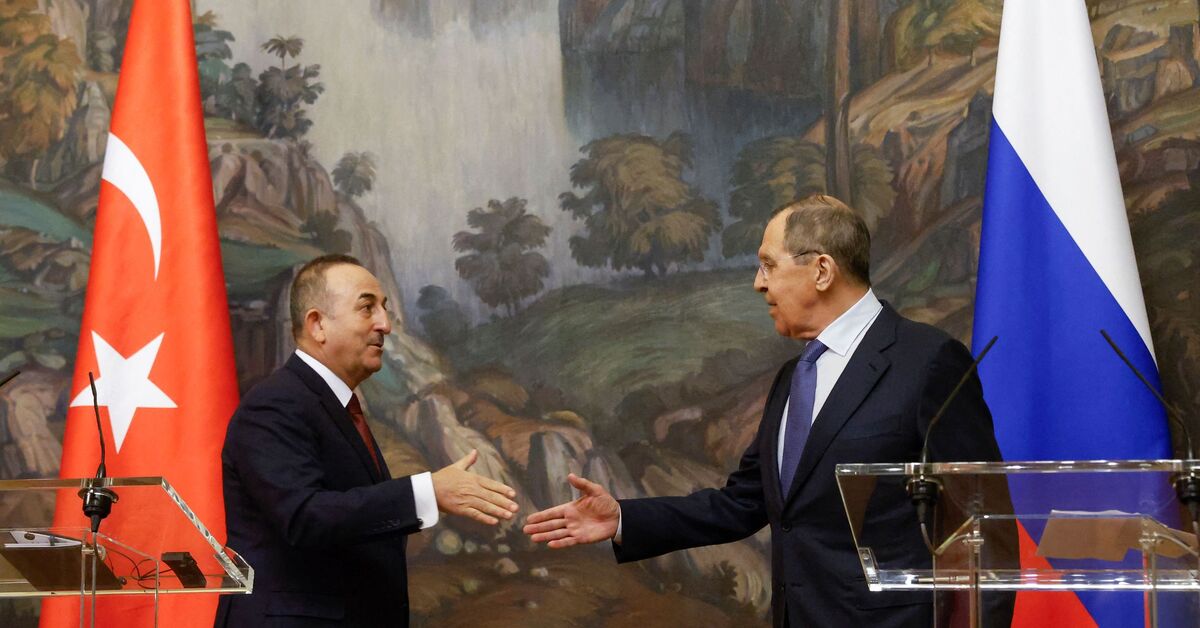

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov is due to visit Turkey on June 8 as Ankara seeks a Russian or American nod to push forward a new military intervention against Kurdish-held areas in northern Syria.

Although Lavrov’s talks in Ankara are expected to focus on the war in Ukraine and its economic ramifications for Turkey, their importance has grown amid threats of intervention from Ankara. Asked about the issue last week, Deputy Foreign Minister Mikhail Bogdanov said Russian officials should talk to their Turkish counterparts first, adding that Defense Ministry officials would accompany Lavrov on the trip. . A foreign ministry spokesman expressed hope that Ankara would avoid measures that would make matters worse in the war-ravaged country.

Speaking in parliament the day before, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan said: “We are entering a new phase in our decision to create a 30-kilometre (18.6-mile) deep security zone along our southern border. We clean up the terrorists from Tel Rifaat and Manbij. He was referring to the People’s Protection Units (YPG), which Ankara says is the franchise of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in Syria. The PKK is designated as a terrorist group by Ankara and much of the international community during its nearly four-decade-long armed campaign in Turkey. Although the Turkish military operation has not officially started, the situation on the lines of contact with the Kurds already resembles a war, barring a ground offensive beyond the lines.

Erdogan should refrain from ordering troops to enter Tel Rifaat and Manbij without a green light from the United States, the Syrian Kurds’ main backer, or Russia, the Syrian government’s main ally. Washington has voiced objections to Turkey’s plans, while messages from Moscow have been more ambiguous since Erdogan first raised the specter of a new operation last month.

While acknowledging Turkey’s security concerns, Moscow suggested that Ankara work with Damascus on the basis of the 1998 Adana agreement on security cooperation between the two countries. Various scenarios can unfold depending on Russia’s attitude.

Turkey’s new intervention plan comes in the context of a squabble over Finland’s and Sweden’s NATO membership bids, with Ankara conditioning their membership on the designation of the YPG and of its political wing, the Democratic Union Party, as terrorist groups, alongside the PKK. Turkey’s friction with its NATO allies suits Moscow’s book, hence the more cautious Russian language on a new Turkish push into Syria. But does Russia’s ambivalence herald the green light sought by Erdogan? Judging by the developments on the ground, that’s not exactly the case.

Russia’s approach appears to be similar to how it acted in 2019, using the pressure exerted by Turkey’s Operation Peace Spring on the Kurds to shift the balance of power in the east. Euphrates. The Russians have increased their presence in the region, as has the Syrian military, in a way that both shrinks the US area of influence and appears to thwart the prospect of a Turkish military push. Russia’s deployment of fighter jets and helicopters at Qamishli airport could be interpreted as a message to deter Turkey, with the helicopters carrying out aerial patrols over areas in Erdogan’s sights. On June 3, the Russians reportedly deployed the Pantsir-S1 air defense system at Qamishli airport. Furthermore, they reportedly deployed additional troops in Ayn Issa, Tel Tamir, Manbij, Kobani and Qamishli, while the Syrian army has reinforced its presence both in Raqqa and north of Aleppo.

Meanwhile, Iran-linked forces sought to advance towards the vicinity of Tel Rifaat. From Iran’s perspective, Tel Rifaat changing hands as a result of a Turkish operation would jeopardize the Shiite settlements of Zahra and Nubl, which lie southwest of the city along the road to the city of Aleppo. Turkey’s state-run Anatolia news agency reported that Iranian-backed forces attempted to deploy Grad missiles in the area on May 30, but were stopped by Russian forces stationed 3 kilometers away. (about 2 miles) west of Tel Rifaat. The next day, the Russians alerted the Kurds and the Syrian army when Iranian-backed forces attempted to enter the vicinity of the YPG-controlled Minnig air base northwest of Tel Rifaat. According to the agency, the Russians also barred Iranian officials from participating in a May 30 meeting with YPG members and Syrian officials.

In past Turkish operations, Russian moves to accommodate Erdogan have been underpinned by the goal of securing critical gains for Damascus, including the return of the Syrian army to the northern regions, and fueling the Turkish-American divisions. By giving the green light to Operation Euphrates Shield in 2016, for example, Russia secured the withdrawal of rebels holding eastern Aleppo. Could it now grant Turkey partial concessions in Tel Rifaat or Manbij without upsetting a large part of the balance of power on the ground in exchange for the reopening of the M4 motorway between Aleppo and Latakia? Or could it allow Erdogan to continue with his safe zone plan in exchange for reversing the status quo in Idlib and withdrawing the armed groups controlling the province? Or could he use Turkey’s firepower as pressure on the Kurds to prepare the ground for a deal that would see the Syrian army take control of Kurdish-held areas?

In 2018, Russia tried unsuccessfully to convince the Kurds to hand over control of Afrin to the Syrian government to prevent Turkey’s Operation Olive Branch. In 2019, Operation Peace Spring was limited to Tell Abyad and Ras al-Ain as Turkey struck deals with the United States and Russia. As a result, Russia secured the return of the Syrian army to a number of regions. Government troops were stationed in Manbij, Tabka, Ayn Issa and Tel Tamir, and a token number of border guards were deployed in areas adjoining Turkey. Ankara’s current “corridor” plan would negate these gains. Moreover, Turkey aims to place its rebel Syrian National Army (SNA) allies in the areas it would seize, and these militias are seen as a common adversary of the Syrian government, Russia, Iran and the YPG-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). Giving the green light to such a Turkish operation could upset the balance Moscow has struck with Damascus and Tehran and completely undermine Russian efforts to drive the Kurds away from Washington and closer to Damascus.

Turkish control of Tel Rifaat would put Aleppo within reach of the Turkish army and the SNA. Aleppo’s northern neighborhoods of Sheikh Maqsood and Ashrafieh are predominantly Kurdish, so access to the road linking Aleppo with Tel Rifaat and Afrin is crucial for Kurds. The Aleppo connection is also important for YPG-controlled areas as a passage to Manbij and the eastern bank of the Euphrates from the Turkish-controlled southern al-Bab. And Manbij, where the Kurds are not the majority, is at a vital point in terms of controlling the M4 highway, which connects the two banks of the Euphrates. Manbij and Tel Rifaat are also of critical strategic importance to the Syrian government. Given all these factors, the prospect of Russia giving up the M4 section linking Aleppo to the northeast seems illogical, not to mention Russia’s constant pressure on Turkey to reopen the western section of the road that links Aleppo to Latakia. .

Nevertheless, the question remains open whether the Russians could grant Turkey certain concessions without earth-shattering consequences in the name of strategic interests beyond Syria. For example, opening up space for Turkey on certain M4 and M5 connections or allowing Turkey to mount a military operation while reserving the Syrian army’s right of response could be questionable possibilities.

If the YPG or the SDF are indeed threats to Turkey’s national security, returning their areas of control to the Syrian state is logically the shortest route to addressing Ankara’s concerns. And that is what Russia means by proposing the Adana agreement as the basis for a solution. Yet without Turkish boots on the ground, Erdogan will be deprived of the victory story he needs at home to bolster his weakened popular support ahead of the election.

In October 2021, Moscow had successfully lobbied for the abandonment of a second Turkish intervention east of the Euphrates, but today, with the Ukraine war on its plate, it seems reluctant to vex Ankara. . And that seems to encourage Erdogan to take risks. Nevertheless, the conditions do not yet seem ripe for mutual concessions on the issue ahead of Lavrov’s visit.

Comments are closed.