The Burmese opposition welcomes the snub of the ASEAN junta and wishes an invitation to the summit

[ad_1]

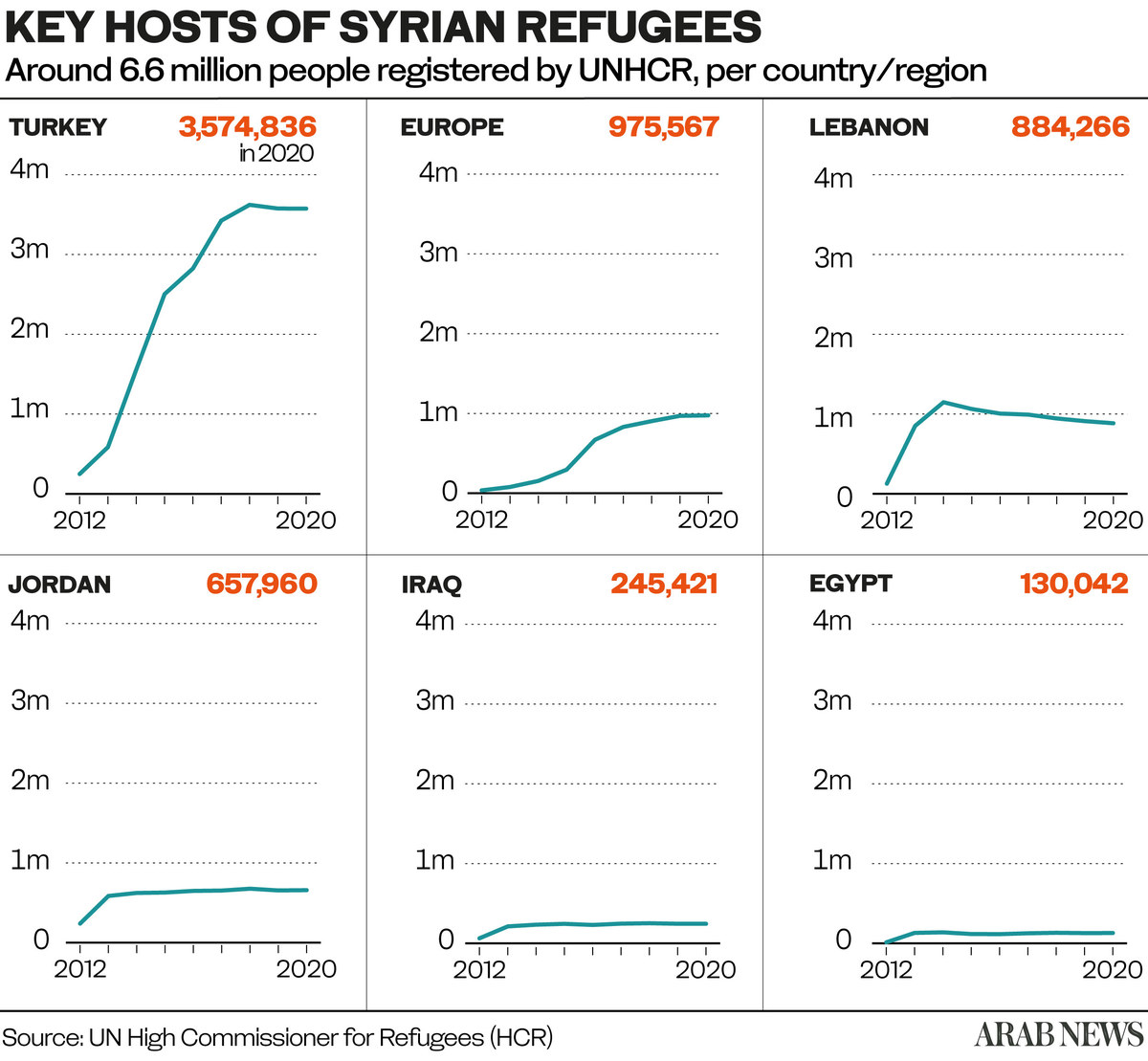

COPENHAGEN, Denmark: As Europe braces for a constant influx of Afghan refugees fleeing the return of the Taliban and economic chaos, a recent shift in political rhetoric indicates Scandinavian countries are less willing to help asylum seekers now than they were in 2015, when they offered sanctuary for tens of thousands of displaced Syrians.

More than 123,000 Afghan civilians were evacuated from Kabul airport by US forces and their coalition partners between August 15, when the Taliban captured the capital, and August 31, when the last foreign troops left. the country.

Many of those who fled were taken to emergency treatment centers in Spain, Germany, Qatar and Uzbekistan. The UN has warned that up to half a million Afghans could flee their country by the end of the year, many seeing Europe as a potential sanctuary.

However, opinions in the once welcoming Scandinavian states of northern Europe appear to have changed over the past six years, with people in those countries increasingly reluctant to open doors for asylum seekers.

“We will never go back to 2015. Sweden will never find itself in this situation again,” Stefan Lofven, Swedish Prime Minister, told the national daily Dagens Nyheter on August 18, three days after the capture of Kabul by the Taliban.

Indeed, as the situation in Afghanistan brings the issue of European asylum policy back to the fore, attitudes in Scandinavia appear to be hardening.

“Denmark first took the nationalist-populist path, followed by Norway,” Swedish Socialist MP Ali Esbati, who has long predicted Sweden will follow suit, told Arab News.

“This is in part due to the fact that many people in Sweden feel that we did what we could in 2015 and that we took the responsibility that a rich country should take when other countries do not. have not. “

Even before the Taliban regained control of Afghanistan, more than 550,000 people in the country were forced to flee their homes this year because of the fighting, according to the UNHCR, the UN refugee agency. In addition to the deteriorating security situation, Afghans are also grappling with severe drought and food shortages, leading to massive internal displacement.

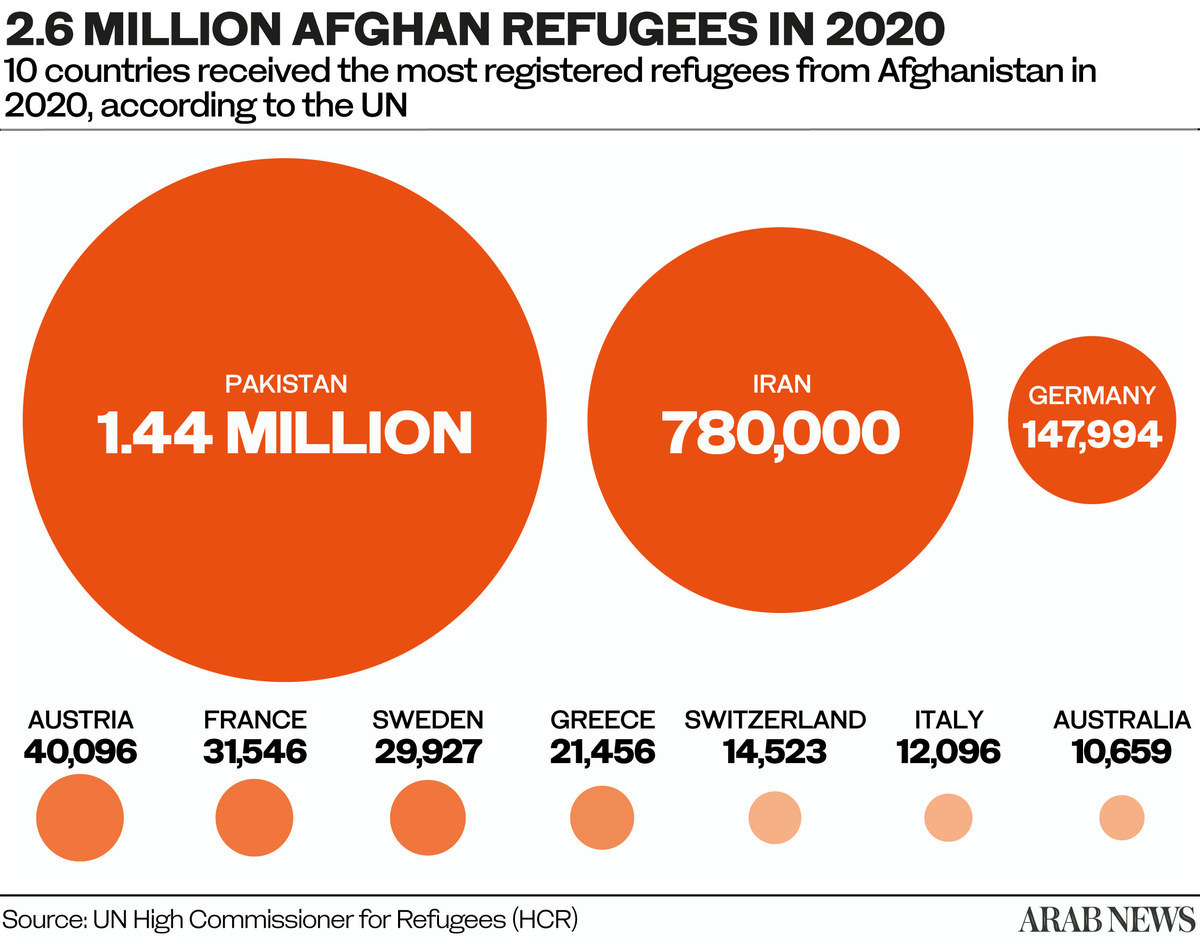

In 2020, nearly 1.5 million Afghans fled to Pakistan and around 780,000 to Iran, according to UNHCR. Germany was third on the list of destinations, with 180,000 Afghans visiting, while Turkey hosted 130,000.

After the fall of Kabul early last month, around 125,000 Afghans sought asylum in Turkey, 33,000 in Germany and 20,000 in Greece.

The French authorities have indicated that they will accept a few refugees but have not specified how many. German authorities did not specify a number either, but Chancellor Angela Merkel said 40,000 people still in Afghanistan may have the right to seek asylum in Germany.

Read the first part of the report: No country for asylum seekers

The UK has said it will welcome 5,000 Afghans this year as part of a program to resettle 20,000 over the next few years. Austria, Poland and Switzerland have said they will not accept any Afghan refugees and have actively tightened border security to prevent attempts to enter the country illegally.

As for Scandinavia, the picture is not clear. After receiving praise for accepting thousands of Syrians at the height of the European refugee crisis in 2015-16, authorities in Sweden, Norway and Denmark appear less willing to shoulder the burden this time around. In fact, the governments of the three nations have not guaranteed even those Syrians who have already granted asylum the right to stay.

This increasingly unwelcoming attitude appears to have developed for a number of reasons, including a housing shortage and a sense of bitterness towards other EU Member States who have not accepted their share of the blame. towards refugees.

An increase in crime is also a factor. In Sweden, for example, first and second generation migrants are over-represented in crime statistics. While the Swedish National Crime Prevention Council has repeatedly warned that there is a difference between correlation and causation, immigration and crime are nonetheless now inextricably linked in the minds of many voters.

It is the same in Denmark. In Copenhagen, social media influencer and political hopeful Hussain Ali said it was time to break with the cultural trait of “berøringsfrygtâ€, which translates into a “fear of touching†sensitive topics.

Ali, a Dane of Iraqi descent, is running for a seat in the city assembly with a Conservative ticket. His passionate social media posts denouncing integration failures regularly attract thousands of likes. He recently suggested that all non-citizens convicted of crimes should be deported.

“There are so many young people who live in a bubble of resentment towards Denmark because they feel alienated,” he told Arab News. “They are stuck between Danish culture and the culture of their parents’ home country.

“I tell them that if they brought their anti-social attitude back to Syria, for example, they wouldn’t last more than a minute without being punished. In the Middle East, you respect your elders – it’s part of their heritage that their parents should teach them.

“They also create harmful stereotypes and prejudices. A lot of my friends are judged by their skin color. People make assumptions about me at first glance.

INNUMBERS

•123,000 – Afghan civilians evacuated from Kabul airport, August 15-31.

• 1,200 – Afghans expelled from the EU in the first half of 2021.

While some might view Ali as a high roller or an upstart, his message clearly struck a chord with many. When he walks through Copenhagen, he is regularly punched by young supporters. But not all the attention he receives is positive.

As he sat in front of a kebab shop during our interview, a young man who appeared to be of immigrant origin shouted at him: “You have sold your soul. Ali stiffened but remained seated.

“This guy is probably just frustrated and stuck in a situation where he has no outlet for his creativity and ambition, despite all the opportunities in Denmark,” he said later.

Although the hardening of attitudes in Sweden and Norway has been less marked than it has been in Denmark, the mood is clearly in the same direction.

“The trajectory is quite typical, really,” said Esbati, the Swedish MP. “First, a nationalist-populist party begins to drum up migration.

“Then there is a kind of breakthrough in the media and in the elections, followed by the conservative parties moving towards the (nationalist-populist) position. And finally the Social Democrats and other left parties are moving in the same direction over time.

On June 23, the Swedish parliament approved a new immigration bill that makes temporary residence permits the norm, just like the Danish system.

“We need an entirely new political (framework) for people to be included in and settle in society,” said Maria Malmer Stenergard, spokeswoman for immigration policy for the Moderate Conservative Party, at the time. of a recent appearance on national radio. “We must start by reducing immigration.

As European states grapple with their collective conscience over how best to balance their duty to protect vulnerable civilians with the desire to preserve their national identity, the growing appeal of the populist right in Scandinavia and elsewhere can only diminish options available to Afghans who are too scared to come home.

Stories of Syrians having firsthand experience of the welcome mat pulled out from under them do not inspire confidence.

Stories of Syrians having firsthand experience of the welcome mat pulled out from under them do not inspire confidence.

Hamdi and Sama Al-Samman were threatened by the Syrian regime in late 2011 for giving food, clothing and blankets to displaced families inside their native Damascus.

“I knew we would be in trouble,†Sama said. “But I couldn’t avoid helping these families.

She added that she had started sleeping in her clothes in case the family had to flee in the middle of the night. When the situation became untenable in January 2013, the couple took their three children to Egypt.

From there Hamid, an electrician by training, traveled to Europe, arriving in Denmark in October 2014.

“We chose Denmark because it would only take me and the children a year to join it,†Sama said. “In Sweden, the family reunification process would take longer.

Hamdi found work easily, and since joining him Sama has been studying Danish so that she can work in the preschool education system. Their daughter Noor, who is in her final year of high school, wants to become an architect.

“Denmark places incredible importance on education,†said Sama. “Our children have opportunities here that they would never have in Syria. Our daughter has opportunities because of gender equality.

The family’s relief was short-lived, however. In January this year, Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen said her goal was to reduce the number of asylum seekers to zero. A few months later, the Al-Sammans were informed that their temporary residence permits would not be renewed. They appeal the decision.

[ad_2]